On Tuesday afternoon, The New York Times revealed that a group of Russian hackers now holds 1.2 billion username and password combinations and over 500 million email addresses. The hacking group, working under the name CyberVor, apparently holds the largest known database of stolen account credentials in the world and appears to be one of the most complex professional hacking outfits out there.

There are a number of things to take away from this discovery: first, many people reuse credentials on multiple websites; second, many websites on the Internet—from the smallest blog to Fortune 500 companies—are still vulnerable to basic attacks by hackers; third and finally (and also feeding back to the first), hackers only need to compromise one account to get at nearly all of your information.

Hold Security, a security firm based out of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, discovered the hacking operation’s database. The New York Times had Hold Security’s copy of the database analyzed by an unaffiliated third party and its authenticity was confirmed. So far, Hold Security has refused to name any websites or victims affected by the hacking group due to non-disclosure agreements—but it is willing to check a website’s security for a nominal fee.

SQL Injections

So how does one accrue 1.2 billion account credentials? There are a variety of ways, but it boils down to three methods: botnets, SQL injections and business deals. Let’s start with SQL injections.

An SQL injection is a type of attack that takes advantage of website weaknesses in an effort to capture user data. It’s a well-known attack that has been in use for over a decade by both hackers and security professionals. While SQL injections are dated, they are effective mainly because many websites either don’t know they’re vulnerable. It’s also because SQL injections can be automated to operate on their own and on a large scale. In this case, the hacking organization sought websites vulnerable to SQL injection by using botnets—the other key element at play.

Botnets typically spread by way of links, emails, and popup ads that aim to trick their victims into downloading malicious software (called malware). This gives the hacker control of the victim’s computer, and it is joined to a larger network of similarly hacked computers to form a botnet. Depending on the goals of the hacker, the botnet can then be used for a variety of malicious purposes, like spreading spam or attacking sites or feeding SQL injections.

Finally, there’s the critical part: the business deals. Business deals are a far less glamorous, but a far more common and realistic depiction of today’s hackers. After all: why go through the trouble of hacking when you can outright purchase (or partner with owners of) databases of compromised accounts for pennies on the dollar? According to The New York Times, this appears to be what CyberVor did.

Yes, it appears the biggest compilation of stolen credentials in the world wasn’t created through a master hacking operation, but rather the conglomeration of disparate hacking groups. And that’s the thing you need to know about professional hackers: they aren’t the James Bond-esque adventurers depicted in the movies, but rather people who operate through trial and error and spreadsheets.

So what does CyberVor do with so many credentials? There are a variety of options at the group’s disposal (or there was, until The New York Times published its report). Options range from culling data off of sensitive websites for identity theft purposes to stealing money from bank accounts, buying gift cards for personal use, or just sending more spam. And it’s that last option that CyberVor is opting to do: spread more spam so their clients (yes, they have clients) can spread more viruses and steal from more people.

So should you be concerned? Maybe—if you use the same email and password for multiple sites. If you do, then yes, you should be very concerned.

Steps to Protect Your Accounts

So let’s say you do have the same username and password for multiple sites. What do you do then? Well, thankfully there are a few steps you can take to fix your situation.

- Change your passwords—all of them. If you use the same login credentials on multiple sites (and you should not), then change your passwords right now. Each login should be unique, between six to eight characters and should include lowercase and uppercase letters as well as numbers and symbols. If you’ve difficulty remembering passwords, then consider a passphrase—a series of random words interspaced with numbers—for extra safety. Better yet, use a password manager and use it to simplify managing all your passwords. For more tips, you can also visit passwordday.org.

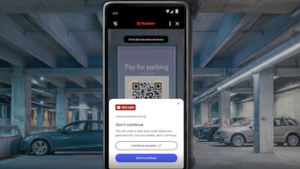

- When available use two-factor authentication. Two-factor authentication is a security feature requiring users to have two things for logging in: something they know, like a password, and something they possess, like a phone. Logging into an account will then require you to type in a code sent through text. It’s cumbersome to some, but it’s also, depending on how it’s implemented, very secure.

- Keep an eye on your bank statements. There is no proof that these hackers have access to your financial accounts directly, but you would be wise to keep an eye on your banking statements just in case. If you see anything odd, contact your bank immediately.

- Protect your computer with comprehensive security. Even the most security-minded of us can be compromised. That’s just an unfortunate axiom of life on the Web. A comprehensive security suite like McAfee LiveSafe™ service can detect and delete malware that finds its way onto your computer. It also comes with a password manager to help you remember all of your logins.