This is the second part of our analysis of the Sandworm OLE zero-day vulnerability and the MS14-060 patch bypass. Check out the first part here.

Microsoft’s Patch

From our previous analysis we’ve learned that the core of this threat is its ability to effectively right-click a file. Now, let’s see what Microsoft did in its patch MS14-060.

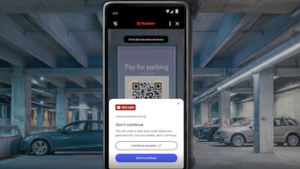

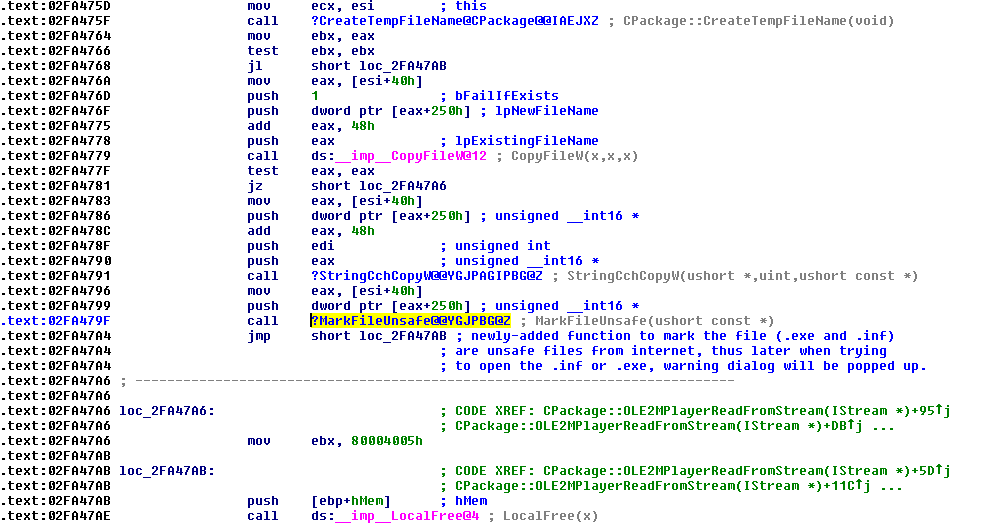

With a little bit of help from patch diffing, we can easily spot that the function MarkFileUnsafe() is called right after the malicious file is dropped into the temp folder. The following image shows the call:

MarkFileUnsafe() is called right after dropping the file into the temp folder.

MarkFileUnsafe() is called right after dropping the file into the temp folder.

There are two ways that an attacker can drop a file into the temp folder. Researchers have seen real in-the-wild samples of both. The first way is to copy from a UNC location, such as in this sample (SHA1: 22fbbcfa5646497e57ee238a180d1b367789984a). The second is to drop it directly from the embedded OLE stream, as in this sample (SHA1: cb2aadbfcfac3c5802ff23ae6971791549b120b8). Our research also shows that the two ways are represented by several code flows. Thus, there have to be (and we have seen them in the updated packager.dll) several places calling the MarkFileUnsafe() function.

Now, let’s take a look at what MarkFileUnsafe() does. The function calls the IZoneIdentifier APIs to mark the dropped file as coming from the Internet zone (“URLZONE_INTERNET”). At a low level, the function leverages a feature in NTFS. (If you’d like more details on how this works, refer to these links 1, 2.) We call this feature Internet marked.

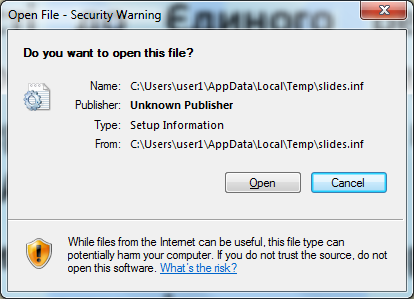

After a file is Internet marked, users will receive a warning dialog whenever they try to “execute” the file. This blocks automatic code execution. For example, installing an Internet-marked .inf file will bring up the following dialog, which is exactly what we saw when testing the original zero-day sample with Microsoft’s patch MS14-060:

Warning dialog when a user tries to “execute” the Internet-marked .inf file.

Warning dialog when a user tries to “execute” the Internet-marked .inf file.

Problem with the patch

An “execute” action will be blocked by the Internet-marked feature because the Windows Shell routines will check the Security Zone when performing an “execute” action. However, a “non-execute” action will go through directly. This is the same reason that we can’t directly run an executable downloaded through Internet Explorer, but we can open a downloaded Word document with Office.

Let’s consider the potential problems:

- On Windows, there are many file types (filename extensions). They are registered by various applications on the system. Taking the same action with right-click pop-up menus basically allows you or a command to run various applications or perform various actions on the system.

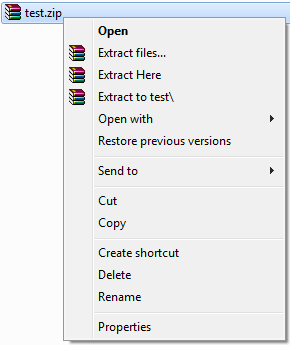

- The registered actions also vary. They can include opening the file, often with the keyword “edit,” as well as many other actions. For example, you can unzip a .zip file when WinRar is installed (see the following image), regardless whether the .zip is Internet marked. It all depends on which extension you choose and which applications you have installed.

The “right-click” menu for a .zip file.

The “right-click” menu for a .zip file.

You can see why we were already worried at this stage: Allowing unexpected applications to run is not acceptable from a security point of view because no one knows whether launching an “unknown” application will cause a problem.

Exploiting the problem: a real-world example

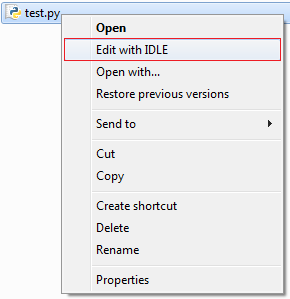

The proof of concept we sent to Microsoft leverages Python on Windows. When we right-click on a .py file, we get this menu:

The “right-click” menu for .py file

The “right-click” menu for .py file

Thus we can call the Python development tool IDLE to open a .py file with the iVerb set to 3, as in the original sample. (See part one of this post for a discussion of iVerb and other details.) Because this is just an “edit” action, even with an Internet-marked file, the command will run without any warning. Now, let’s see what happens when IDLE runs. We use Process Monitor to record the following events:

It seems that IDLE tried to load a Python module named tabnanny in the same directory as the .py file. This interested us. So we created tabnanny.py and test.py in the same directory. When opening test.py with IDLE (through right-clicking), the code inside tabnanny.py was automatically executed!

As we have mentioned, the first security issue in packager.dll is allowing it to drop arbitrary files into the temp folder. By embedding more Packager objects on a PowerPoint slide, we can drop many files into the temp folder when a PowerPoint Show slide is viewed. Thus we can drop the first file with the special filename tabnanny.py. When the second .py file, with any filename, is opened by IDLE, the Python code in tabnanny.py will immediately be executed.

The environment is Windows 7 with Office 2010 and Python 2.7.8 installed, all are updated after the October patch (with MS14-060 installed) but before the November 11 patch.

Even though we ran the exploit in an environment with third-party software installed, considering the large number of file types on default Windows as well as various “non-execute” actions for these file types, there is a good chance that attackers can develop exploits for the default setup.

A look at the partial bypass

The preceding exploitation method was the one we showed to Microsoft. As we have mentioned at the beginning of this post, there is an in-the-wild sample that is claimed to also bypass the patch. We’ve obtained that sample (SHA1: cb2aadbfcfac3c5802ff23ae6971791549b120b8). Let’s see how it works.

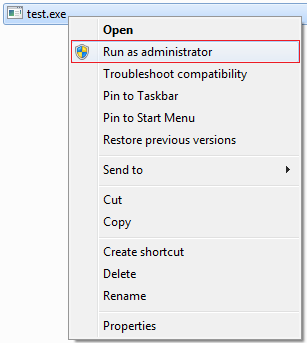

This sample drops an .exe file into the temp folder, and also selects the second item on the right-click menu (via cmd=3). What’s the second item for an .exe on Windows?

The right-click menu for a Windows .exe file.

The right-click menu for a Windows .exe file.

Now, we see that the exploit performs “Run as administrator.” This won’t trigger the Internet-mark warning dialog because it triggers another dialog: a user account control dialog will show up when the UAC is not disabled for a standard user account.

Concerns remain

Microsoft has finally resolved this serious vulnerability with MS14-064. Users should apply the patch as soon as possible. As we have pointed out in previous sections, the vulnerability actually consists of two security issues: the “dropping arbitrary file into temp folder” issue and the “code execution through DoVerb()” issue. However, according to our test against the new patch, only the latter was fixed; the “dropping arbitrary file into temp folder” issue remains. We recommend that Microsoft resolve this security issue as well.

Users who have concerns regarding the remaining issue may consider the workaround and mitigations provided in our July post.

Conclusion

In this post we provided in-depth research around the Sandworm vulnerability CVE-2014-4114, which includes a thorough understanding of the root cause, the exploitation, the patching methodology, as well as the patch bypassing that leads to CVE-2014-6352. We demonstrated a real-world bypass that leverages an issue in Python IDLE.

The key problem of the patch is that it blocks only a small number of actions of the right-click menu involved with direct execution. However, other actions, such as the most popular–“editing” with a registered application–are still allowed. This interoperability opens a door for attackers for future exploitation.

This interesting case study highlights that interoperability between applications raises complexity. Security is no longer about a single application. Understanding the behaviors of various applications and how they work together is vital for effective security.

Thanks to my colleagues Bing Sun, Chong Xu, Stanley Zhu (all of McAfee Labs), and Xiaoning Li (McAfee) for their help with this analysis.