On Monday Kaspersky Labs announced the discovery of a large number of malware infections across large parts of the globe. Kaspersky has named this attack Careto, after what appears to be an internal name used by the attackers for one of the malware families involved. (The word careto in Spanish means ugly face or mask and is derived from an ancient religious ritual in Portugal.)

These infections involve components whose capabilities include:

- Stealth rootkit to hide its files and network traffic

- Sophisticated information-gathering tools to enumerate hardware and software configurations

- User account information stealing

- PGP key theft

- Uploading of user files

- Downloading of new and updated malware

The samples that we at McAfee Labs have seen suggest that this attack has been going on since 2007. If that is the case, the attackers have been very successful in both deploying and maintaining their malware unnoticed. The ramifications of this attack are likely to be serious and may come to light only after much more research and analysis.

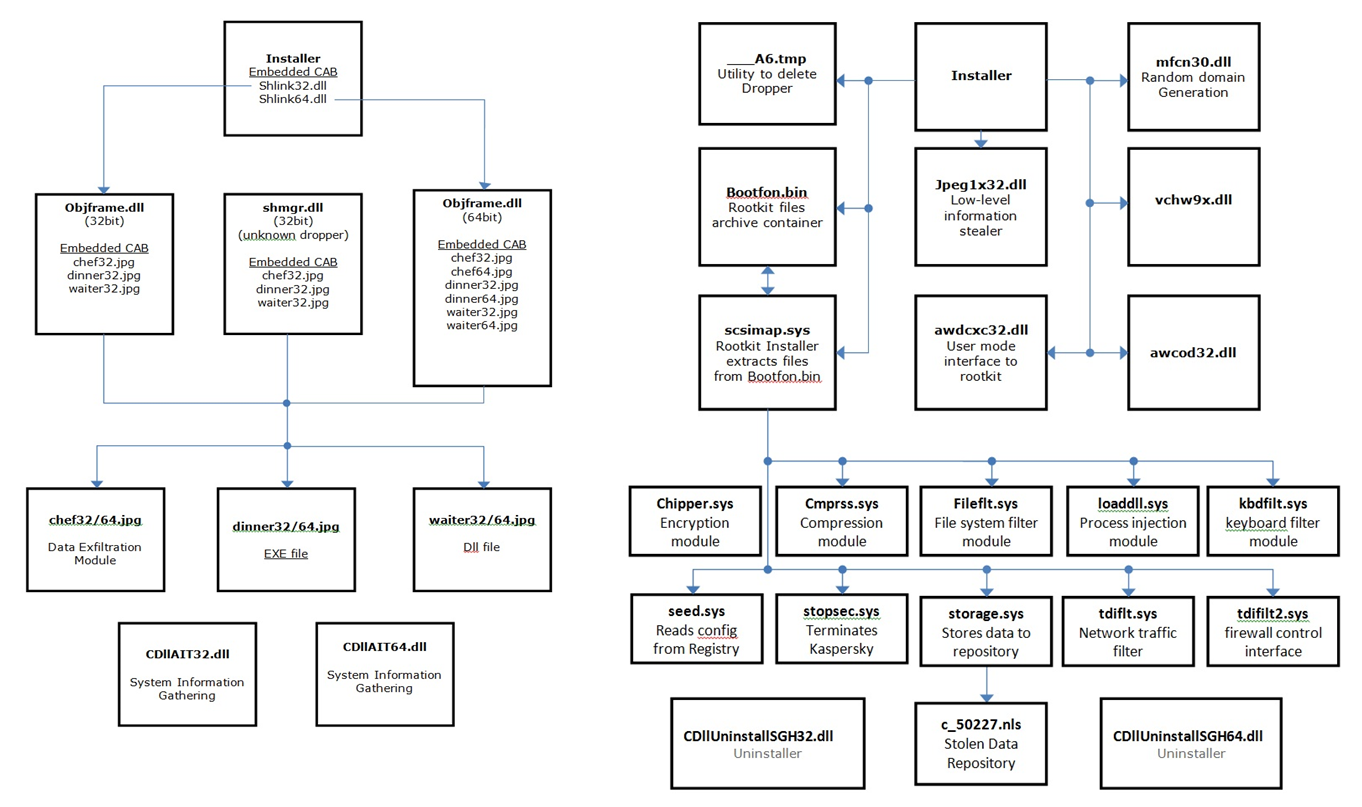

While analyzing this malware, we very quickly realized that this would be no easy task. Starting with two simple installers we rapidly ended up with 39 files to analyze and reverse-engineer. To further complicate matters, several parts of the malware were resistant to standard analysis techniques and required in depth reverse engineering. As we slowly peeled away the layers, we found a highly sophisticated attack requiring a lot of analysis. The number of components involved and the use of on-demand encoding and decoding of strings by a modified RC4 algorithm gave us insight into Careto’s complexity. In this post we offer a preview. For a more detailed description of various modules, please refer to this McAfee Labs Threat Advisory.

The malware involved in this attack seems to be divided roughly into two separate groups: Careto and SGH. Both of these families are extremely modular in their design, allowing for very simple maintenance and upgrading because only small components are required rather than a single large file. The attackers clearly had a long-term view when they were developing this malware.

Custom Encryption

One of the first things we found when we started digging into the samples was the extensive use of encryption to obfuscate both incriminating strings and data objects that the malware used in its attack. These objects included both a payload file for dropping and configuration data blocks.

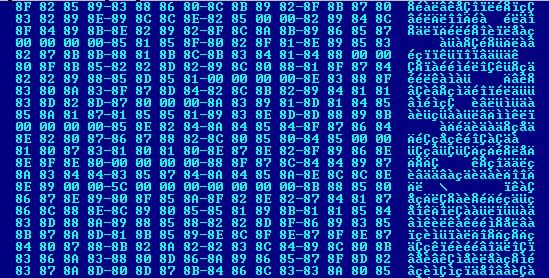

The encryption code looked familiar and in many ways resembled RC4; however, detailed analysis revealed that they were using a modified algorithm. The strings in every sample were encrypted using a custom RC4 algorithm along with an entropy-equalizer function to prevent automated systems from detecting anomalies.

Each encrypted character appears to be added with 0x80 like so:

Before being passed to the custom RC4 function, each character is decoded using the following function:

char decode_character(char* encryptedString, int index){ char ret = 0;

ret = 16 * (encryptedString[ 2 * index] – 0x80);

ret |= encryptedString[(2 * index) + 1] – 0x80;

return ret; }

Basically, information stored in one encrypted byte is split across two bytes, thereby doubling the size of each encrypted string. Once a character has been decoded, it is passed to the custom RC4 function, which is similar to the original RC4 design with the following changes:

- S-Box size has increased from 256 elements to 260 elements

- The counter runs from 255 to 0 instead of 0 to 255 in RC4’s KSA loop

- Inside the KSA loop, if a value to be swapped is greater than the current counter value, a new value to be swapped is found

The first character of the RC4 decryption result is ignored, while the rest comprises the decrypted string.

Once we could decrypt the encoded strings, we thought we would have the malware cracked; but then we found that the attackers had another trick up their sleeves. Once decrypted, one of the encrypted strings appeared to be yet another encryption key. Sure enough, by examining the code we saw that this key was used to decrypt a further block of data–this time using what looked like standard RC4 encryption. This step finally enabled us to decrypt the payload of the droppers and unravel the malware in all its complexity.

Data Theft

Our analysis revealed data and information theft on a large scale. The initial malware samples exhibited some fairly basic information-gathering capabilities–such as user account name, system name, basic network configuration, etc. However, the malware’s modular design makes it easy to download additional malware modules to plug into the architecture. These data-gathering capabilities exceed pretty much everything else we have seen to date. The malware can gather around 100 data points in the following categories:

- Operating system

- Local user accounts

- Hardware

- Memory

- File system

- USB devices

- Running processes

- Installed software

- Network information

- Software

- Hardware

- Network

- Snapshot

- Private credentials

Victims of this attack include government institutions and embassies, gas and oil companies, scientific research organizations, and political activists. This is an attack of immense scale.

Our analysis of this malware is ongoing. We will publish further information as it comes to light. The full technical details of our analysis can be found in the McAfee Labs Threat Advisory.

We thank our colleagues Volodymyr Pikhur, Suriya Natarajan and Mark Olea for their analysis.