If you are like me, there are times when you will misplace your hotel key. Times when you’re switching a bucket of ice between hands while searching your pockets or bag. Wondering if you’ve left the key in your room or possibly the lobby. Thinking “I’ve always got my phone on me, wouldn’t it be so much easier if I could use it to open the door.” OK, maybe I’ve never thought that last bit, but the folks at high-security lock makers Assa Abloy apparently have. They’re running a four-month trial of their Mobile Key technology at the Clarion Hotel in Stockholm. Essentially a guest checks in with a phone and the room key is sent directly to the device. No more misplaced keys.

The hotel trial is a joint effort among Choice Hotels Scandinavia, mobile carrier TeliaSonera, and near field communications (NFC) vendor Venyon. NFC is an extension of the same technology used in “tap and pay” credit cards. NFC turns your phone into a mobile wallet. In this case, just tap your NFC-enabled phone next to the hotel door knob and it unlocks.

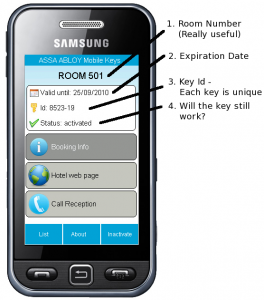

Assa Abloy has an interesting video showing off the many uses of their Mobile Keys (house key, office key, temporary key for contractors, hotel keys, etc.). You can issue temporary keys to contractors or cleaners, and you receive a notification whenever one of the temporary keys is used. In the same way, when you check in to a hotel using your phone, they can send your hotel key directly to your phone.

Because most people don’t have NFC-enabled phones, the Clarion’s guests are given new versions of a Samsung phone. The Samsung S5230 was a popular touch-screen phone released last year, and this year it’s been updated for NFC. So for the moment guests will still carry multiple devices–two phones–but eventually we expect to use one smartphone for nearly everything.

NFC security

NFC phones sound like a great improvement over hotel keys and keycards. If you’re like me, however, you’re probably wondering how it could all go horribly wrong–especially if you’re familiar with Collin Mulliner’s security research on NFC-enabled phones.

Mulliner took a look at a number of Nokia NFC phones. He tried a number of attacks against the devices: phishing, fuzzing, spoofing. He also developed a python library and tools to read and create NFC tags. This library generated a number of specially crafted tags to fuzz the NFC reader on the Nokia 6131. This research isn’t current for the latest NFC phones, but it serves as a basis for expanding to new devices.

Unlike the Nokia 6131, the Samsung S5230 supports the Security and Trust Services API for the J2ME (JSR-177) standard for secure distribution of Mobile Keys. This is basically using public key encryption to ensure that the key your phone receives came from the hotel (no spoofing attacks) and that it hasn’t been tampered with on the way (no man in the middle attacks).

Your phone’s accepting a fake key isn’t the most likely attack. An attacker or thief would rather get the actual key or, in this case, an electronic copy of your key. With NFC and other RFID systems, there’s an attack called ghost and leech, or simply a relay attack. Here’s a quote from the first paper to mention the attack: “The ghost is a device which fakes a card to the reader, and the leech is a device which fakes a reader to the card.” An attacker would either need to steal an actual reader (from a hotel door) or manufacture a compatible reader to function as the leech, and similarly clone the hardware used in your phone to play back the Mobile Key to your hotel room’s door as the ghost. It’s difficult for attackers to get access to the hardware during a trial, but once the hardware is widely in use there will be opportunities to acquire it. We’ve already seen as much with RFID credit card readers sold on eBay.

These are attacks that attempt to intercept the key during transit or block it from arriving on your phone. There is still the possibility that an attacker will go after the device that holds the key or the mobile app that interfaces with the NFC hardware. The Samsung S5230 is a J2ME device and the Mobile Keys app is very likely a Java program. Generally the threats we’ve seen on J2ME phones have been Trojan horse programs, designed to trick users into harming themselves or costing them money. It’s unlikely that a Trojan could properly convince a user to install it in place of the legitimate Mobile Keys app. It would make more sense, as on platforms such as Android, to go after the underlying operating system or Java Virtual Machine (JVM). Two years ago security researcher Adam Gowdiak exposed vulnerabilities in the JVM used by a number of well-known mobile phones. He developed a number of proof-of-concept exploits and malware targeting the JVM. Given that the flaws were in the JVM and not in the applications, the fixes would require a firmware update on affected phones. Although these threats are more difficult to defend against, they also require a much higher skill level and a greater amount of work from an attacker.

For the moment these are either old or theoretical attacks. We still have some time before attackers and thieves catch up to the new technology. I hope the trials will go well and in the near future I won’t need to shuffle things around in my arms to hunt down that elusive hotel key. But finding my misplaced mobile phone is another story.=”/blogs/wp-content/uploads/